lobsterman n.

1823, American English, from lobster (n.) + man (n.).

Entries linking to lobsterman

large, long-tailed, stalk-eyed, 10-legged marine shellfish (Homarus vulgaris), early Middle English lopster, lopister, from Old English loppestre "

The change of Latin -c- to English -p- (and, from late 14c., to -b-) is unexplained; perhaps it is by influence of Old English loppe, lobbe "

OED says the Latin word originally meant "

As slang for "

Sir William Waller having received from London [in June 1643] a fresh regiment of five hundred horse, under the command of sir Arthur Haslerigge, which were so prodigiously armed that they were called by the other side the regiment of lobsters, because of their bright iron shells with which they were covered, being perfect curasseers. [Lord Clarendon, "History of the Rebellion," 1647]

"

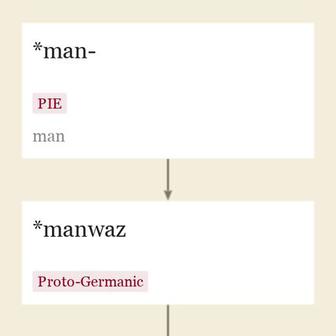

Sometimes connected to root *men- (1) "

Specific sense of "

Man also was in Old English as an indefinite pronoun, "

As "

Man-about-town "

So I am as he that seythe, 'Come hyddr John, my man.' [1473]

MANTRAP, a woman's commodity. [Grose, "Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue," London, 1785]

At the kinges court, my brother, Ech man for himself. [Chaucer, "Knight's Tale," c. 1386]

updated on September 04, 2016