law-breaker n.

also lawbreaker, mid-15c., from law (n.) + agent noun from break (v.). Old English had lahbreca.

Entries linking to law-breaker

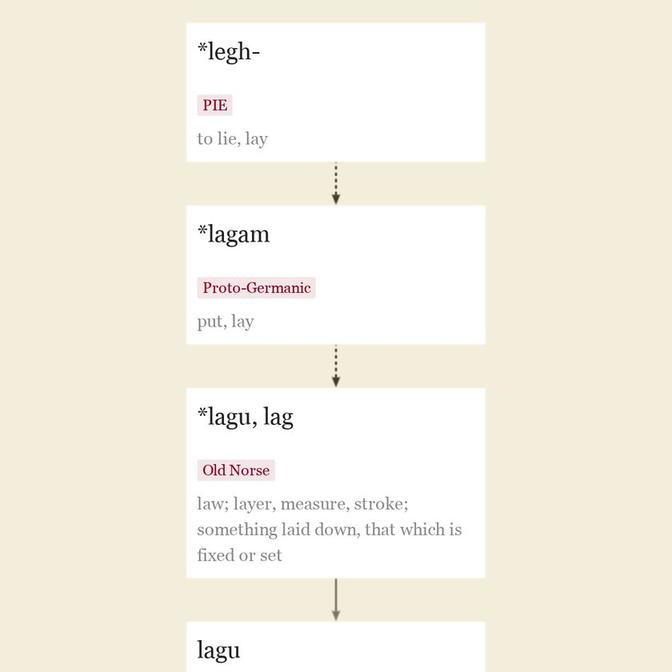

Old English lagu (plural laga, combining form lah-) "

This is reconstructed to be from Proto-Germanic *lagam "

Rare in Old English, it ousted the more usual ae and also gesetnes, which also were etymologically "

In physics, "

It is more common for Indo-European languages to use different words for "

Indo-European words for "

Words for "

[L]earn to obey good laws before you seek to alter bad ones [Ruskin, "Fors Clavigera"]

Old English brecan "

Closely related to breach (n.), brake (n.1), brick (n.). The old past tense brake is obsolete or archaic; the past participle is broken, but shortened form broke is attested from 14c. and was "

Of bones in Old English. Formerly also of cloth, paper, etc. The meaning "

In reference to the heart from early 13c. (intransitive); to break (someone's) heart is late 14c. Break bread "

The ironic theatrical good luck formula break a leg (by 1948, said to be from at least 1920s) has parallels in German Hals- und Beinbruch "

updated on October 10, 2017