commedia dell'arte n.

"

Entries linking to commedia dell'arte

late 14c., "

The passage on the nature of comedy in the Poetic of Aristotle is unfortunately lost, but if we can trust stray hints on the subject, his definition of comedy (which applied mainly to Menander) ran parallel to that of tragedy, and described the art as a purification of certain affections of our nature, not by terror and pity, but by laughter and ridicule. [Rev. J.P. Mahaffy, "A History of Classical Greek Literature," London, 1895]

The origin of Greek komos is uncertain; perhaps it is from a PIE *komso- "

The classical sense of the word was "

Comedy aims at entertaining by the fidelity with which it presents life as we know it, farce at raising laughter by the outrageous absurdity of the situation or characters exhibited, & burlesque at tickling the fancy of the audience by caricaturing plays or actors with whose style it is familiar. [Fowler]

Meaning "

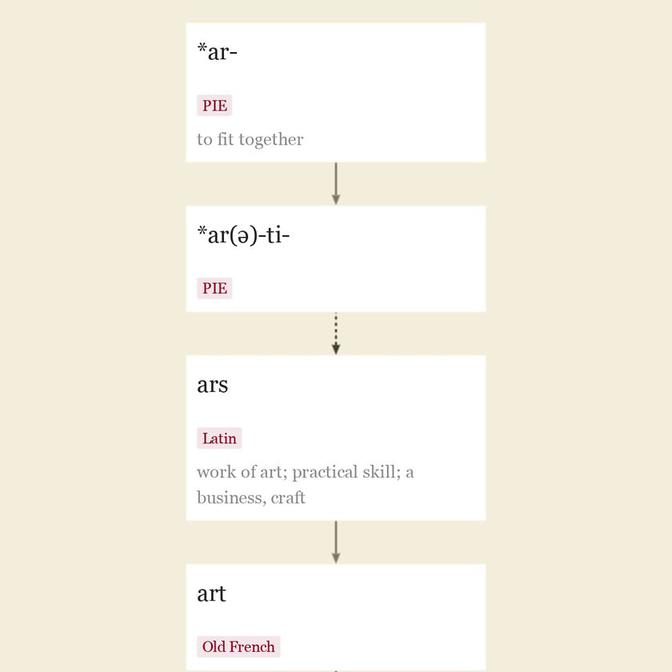

early 13c., "

In Middle English usually with a sense of "

In science you must not talk before you know. In art you must not talk before you do. In literature you must not talk before you think. [Ruskin, "The Eagle's Nest," 1872]

Supreme art is a traditional statement of certain heroic and religious truths, passed on from age to age, modified by individual genius, but never abandoned. The revolt of individualism came because the tradition had become degraded, or rather because a spurious copy had been accepted in its stead. [William Butler Yeats, journal, 1909]

Expression art for art's sake (1824) translates French l'art pour l'art. First record of art critic is from 1847. Arts and crafts "

updated on March 06, 2018