check-book n.

also checkbook, cheque-book, "

Entries linking to check-book

c. 1300, in chess, "

As "

Hence: "

From its use in chess the word has been widely transferred in French and English. In the sense-extension, the sb. and vb. have acted and reacted on each other, so that it is difficult to trace and exhibit the order in which special senses arose [OED]

The meaning "

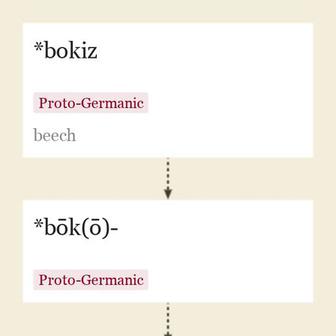

Middle English bok, from Old English boc "

Latin and Sanskrit also have words for "

The sense gradually narrowed by early Middle English to "

The use of books or written charters was introduced in Anglo-Saxon times by the ecclesiastics, as affording more permanent and satisfactory evidence of a grant or conveyance of land than the symbolical or actual delivery of possession before witnesses, which was the method then in vogue. [Century Dictionary]

From c. 1200 as "

updated on November 06, 2017